An Introduction to USB Protocol

24 August 2015

In order to begin fulfilling the first item on the Remote Xbox checklist a I needed to find an input controller. Fortunately, I happened to have a wired Xbox 360 controller that I could use. That left me with having to figure out how to extract the inputs using the raspberry pi. It turns out that there are plenty of pre-existing solutions to solve this problem, including using xboxdrv combined with pygame as described here by Martin O’Hanlon in his post on using an Xbox controller to control a robot. However, it seemed like it would be more fun to figure things out from the beginning myself and as such would require me to carry out some research on how USB devices actually work. This led me to the websites USB Made Simple, Beyond Logic’s USB in a NutShell and Microsoft’s Concepts for all USB developers .

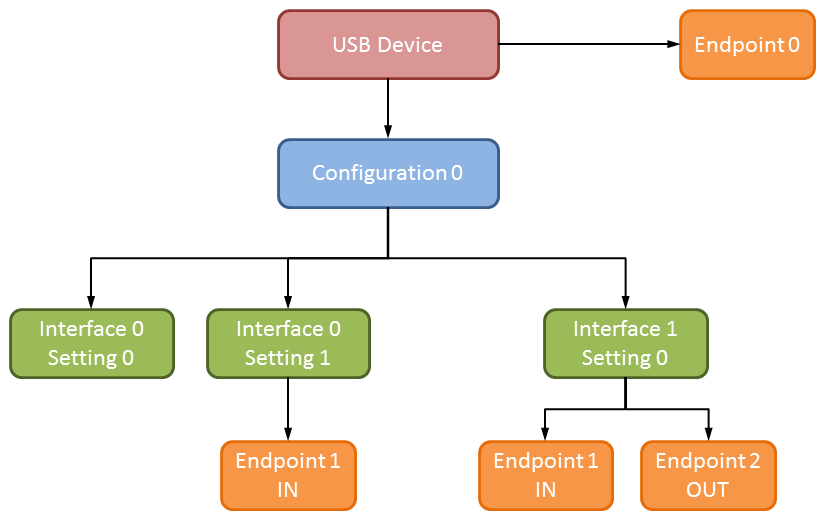

These sources provided me with a rudimentary knowledge of USB devices, enough to get started with anyway. Essentially, in addition to a Vendor and Product identifiers, USB devices feature Configurations, Interfaces and Endpoints, a combination of which control how the device works. The top level is the Configuration which controls what the device does. Whilst a device can have more than one Configuration associated with it, only one can be active at any time, and it is selected by the device driver. A given Configuration can have a number of Interfaces which specifies the functions of the device, usually one function per Interface. Again, Interfaces can have alternate settings associated with them and only one can be active at once. Finally, Interfaces have Endpoints which are used to transfer the data in and out of the device and cannot be shared between Interfaces.

Every USB device must assign a bidirectional control Endpoint at the 0 address. This is so information about the device can be obtained and the Configuration for the device can be set. The data Endpoints are unidirectional (IN or OUT) and have one of four types (control, interrupt, isochronous and bulk). IN and OUT are relative to the host, so IN is a transfer from the device to the host whilst OUT is a transfer from the host to the device. A typical example of a USB device using Figure 1 would be that of a webcam with a built-in microphone and speaker. Here Interface 0 would correspond to the camera of the device. The Alternate Setting 0 would be active when the camera is not in use to save bandwidth as it has no Endpoint associated with it. Alternative Setting 1 would be active when the camera is in use and the IN Endpoint is used to transfer the video data from the camera to the host. Interface 1 would correspond to the microphone and speaker, where Endpoint 1 would take noise detected by the microphone and transfer it the host whilst Endpoint two would take data from the host and output it from the speaker.

As mentioned above, there are four different types of transfer available for an Endpoint. The transfer types each have their own properties which makes them suitable for different applications. Control transfers are used by Endpoint 0 when configuring the device and are used for command and status operations. Interrupt transfers are used to provide regular status updates from a device and have included error checking so the data arrives error free. Isochronous transfers are used to transfer large amounts of time sensitive data, such as video or audio streams, where it is less important if a packet of data is dropped on the way. Bulk transfers are also used to transfer large amounts of data, however, they are assigned the remaining bandwidth that has not already been allocated to interrupt and isochronous transfers. As such, they are primarily used for non-time critical applications, such as print jobs, and they are error checked with guaranteed delivery unlike isochronous transfer. So for the example above the camera Endpoint would use isochronous transfer whilst the microphone/speaker Endpoints would likely use interrupt transfer.